(cross-posted from my substack)

Go With the Flow?

Thoughts after reading Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

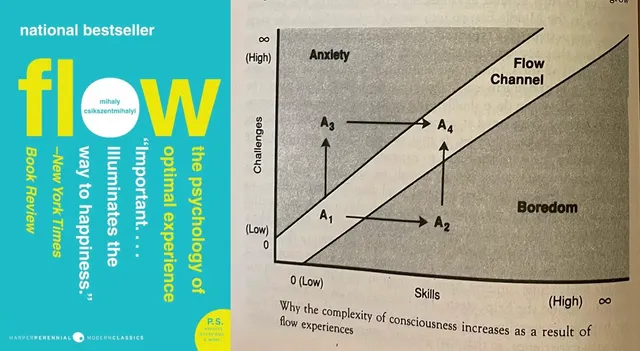

The concept of the “flow state” popularized by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi is frequently mentioned in the context of games and gamification. Although I’m familiar with the “pop” version of the idea from things I’ve read and seen I figured it was worth going to the source to see whether the ideas were worth exploring, so I read Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, his book on the topic. I haven’t looked into the scholarly papers or later research, but based on the book my conclusion is that there’s not much here, especially for people engaged in games and game design.

What’s the big idea?

The core premise is that there’s a human psychological state, distinct from pleasure, that’s consistently associated with positive, enjoyable experiences. It’s the fully-engaged feeling of being “in the zone”:

When people ponder further about what makes their lives rewarding, they tend to move beyond pleasant memories and begin to remember other events, other experiences that overlap with pleasurable ones but fall into a category that deserves a separate name: enjoyment. Enjoyable events occur when a person has not only met some prior expectation or satisfied a need or a desire but also gone beyond what he or she has been programmed to do and achieved something unexpected, perhaps something even unimagined before.

Enjoyment is characterized by this forward movement: by a sense of novelty, of accomplishment. Playing a close game of tennis that stretches one’s ability is enjoyable, as is reading a book that reveals things in a new light, as is having a conversation that leads us to express ideas we didn’t know we had. Closing a contested business deal, or any piece of work well done, is enjoyable. None of these experiences may be particularly pleasurable at the time they are taking place, but afterward we think back on them and say, “That really was fun” and wish they would happen again. After an enjoyable event we know that we have changed, that our self has grown: in some respect, we have become more complex as a result of it.

That seems plausible to me, trying to categorize subjective experiences is always tricky but calling this a distinct and recognizable state may very well be reasonable. I think it’s also worth taking note that enjoyed things don’t have to be pleasurable in the moment – enjoyment seems like something more textured or nuanced than a simple function of pleasure (perhaps similar to how a drama can be compelling and satisfying even if, moment-by-moment, it’s bringing up traditionally negatively-valenced emotions).

How do you do it?

Csikszentmihalyi focuses heavily on goals, skills, clear rules, and feedback as the drivers of flow. The idea is that if a person’s skills are a good match for the challenge they’re facing then it’s a compelling, engrossing experience. If there’s a mismatch then things like self-consciousness, anxiety, or boredom will tend to creep in. If a challenge seem trivial relative to your skills you’ll likely be bored by it, if the challenge is more than you can handle with your skills you’ll likely feel overwhelmed or anxious, but if you are in the sweet spot where you’re operating at the frontier of your ability then it will often be a fully engrossing activity that leaves you feeling fulfilled, and maybe even like you’ve grown or expanded. The feedback and rules elements are important for being able to understand how you’re doing, if you can’t tell if your actions are working or not then it’s hard to meaningfully engage with an activity or know if your skills are doing the right thing.

But we have seen how people describe the common characteristics of optimal experience: a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems. Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted. An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult, or dangerous.

So what’s not to like?

The basic story seems fine as far as it goes, and seems to map readily to some things that are enjoyable experiences, like engaging in a competitive game with a closely-matched opponent. But the impression I get is that the idea went from “games are often flow experiences, lets start from there” to consulting previous games scholarship to suggest ideas, then looking through confirmation-bias lenses to detect those patterns in other enjoyable activities. So I have a few issues.

“Goals” aren’t the be-all end-all.

It’s common to think that clear goals are an essential feature of games (the philosopher Bernard Suits, for example, included striving for a goal in his proposed formal definition), and many games do have them. But I think the function of goals and win-conditions is to orient the players within the game, and it’s the orienting that does the important work rather than other aspects of goals such as being achievable (and achieving the win condition of a game generally causes the game to end, so actually achieving them rarely happens within a game). Clear goals are one good way of doing this, so many games use this element in their design, but it seems to me that goals are a subset of things that can provide that orienting function, not the whole category of things. (The common response is to claim that these non-goal-based games have implicit goals, but when articulated these supposed implicit goals often have a “tacked-on” feel that strike me as akin to the “add more epicycles” approach that philosophers of science attribute to people trying to preserve flawed paradigms).

The goals of an activity are not always as clear as those of tennis, and the feedback is often more ambiguous than the simple “I am not falling” information processed by the climber. A composer of music, for instance, may know that he wishes to write a song, or a flute concerto, but other than that, his goals are usually quite vague. And how does he know whether the notes he is writing down are “right” or “wrong”? The same situation holds true for the artist painting a picture, and for all activities that are creative or open-ended in nature. But these are all exceptions that prove the rule: unless a person learns to set goals and to recognize and gauge feedback in such activities, she will not enjoy them.

No, huge swaths of human activity that involve flow experience aren’t “exceptions that prove the rule”, they’re exceptions that should lead you back to the drawing board!

Csikszentmihalyi himself even deploys a parallel “it’s about the structure of the activity, which the goal merely informs” argument when making the case that Yoga spiritual practices are similar to, rather than distinct from, “Flow” despite Yoga having an end-goal of achieving a final stage of enlightenment:

But this opposition my be more superficial than real. After all, seven of the eight stages of Yoga involve building up increasingly higher levels of skill in controlling consciousness. Samadhi and the liberation that is supposed to follow it may not, in the end, be that significant—they may in one sense be regarded as the justification of the activity that takes places in the previous seven stages, just as the peak of the mountain is important only because it justifies climbing, which is the real goal of the enterprise.

Skills and challenges aren’t readily measurable

In a lot of activities it makes sense to think of being able to improve a skill, or a skill level being adequate for some particular task, so skill can seem like a quantifiable trait that someone has. Similarly, easy things seem like they have less difficulty than hard things, so it seems like there must be some quantifiable “how difficult” or “how challenging” trait that things have. This may sound good in the abstract, or relative to a particular situation (e.g. “that challenge was too difficult for me”), but unlike qualities like height or weight it’s hard figure out what the levels of these traits are in any given instance, even if they could be real. Humans don’t have RPG-style skill ratings in real life, we don’t have any difficult-ometers we can point at a task to see how hard it is to do. Evaluating someone’s level of skill is really difficult, even in areas where we have lots of data and concrete measurements, such as professional sports. So the nice skill/challenge diagram I included at the top of this post seems like a nice story, but is it a story you can use if you need to dig into the particulars of a situation?

What even is a skill?

We often talk about “skill” like we know what it means, but it’s not obvious that you can easily carve nature at the joints to figure out what counts as an individual skill. Is golf a skill? Are regular swings and putting different skills? Do woods and irons involve different skills? Does hitting the ball from the fairway, rough, or sand involve different skills or the same one?

So is there anything here?

Part of my frustration with the book is that I think I agree with Csikszentmihalyi on many of the big-picture aspects he talks about, but I don’t think his low-level construct is very compelling and don’t think he does the work to tie his low-level ideas to his big picture. (Another frustration is that it was a real slog to read). There’s also a rigidity to the “building skills” framing that rubs me the wrong way (that may be one way to look at things, but likely not the only way). When he talks about engaging with the environment and the possibility of living your life as a fully-integrated flow activity it seems to have some parallels with the way I’ve been thinking of games recently, such as wanting amount of information in the immediate environment to be “matched” with a player’s ability to process it, thinking of players as elements in a dynamic system, as well as games, art, and life having microcosm/macrocosm relationships with each other. For example:

Basically, to arrive at this level of self-assurance once must trust oneself, one’s environment, and one’s place in it. A good pilot knows her skills, has confidence in the machine she is flying, and is aware of what actions are required in case of a hurricane, or in case the wings ice over. Therefore she is confident in her ability to cope with whatever weather conditions may arise—not because she will force the plane to obey her will, but because she will be the instrument for matching the properties of the plane to the conditions of the air. As such she is an indispensable link for the safety of the plane, but it is only as a link—as a catalyst, as a component of the air-plane-person system, obeying the rules of that system—that she can achieve her goal.

and

Whereas a conventional artists starts painting a canvas knowing what she wants to paint, and holds to her original intention until the work is finished, an original artist with equal technical training commences with a deeply felt but undefined goal in mind, keeps modifying the picture in response to the unexpected colors and shapes emerging on the canvas, and ends up with a finished work that probably will not resemble anything she started out with. If the artist is responsive to her inner feelings, knows what she likes and does not like, and pays attention to what is happening on the canvas, a good painting is bound to emerge. On the other hand, if she holds on to a preconceived notion of what the painting should look like, without responding to the possibilities suggested by the forms developing before her, the painting is likely to be trite.

I like those quotes, but they strike me as philosophical or spiritual, not grounded in concrete empirical psychology. They may be true, but I am skeptical that his psychological research shows they are true and connects all the links in the chain. It has the same feel to me as when a social psychologist uses the results of some limited experiment to say that it explains the important things happening in politics: it’s more likely that you’re just engaging in social commentary with a research-paper fig leaf. It doesn’t mean the commentary is wrong, but it’s probably getting way out ahead of what’s solid.

The Circle of Life

If, as I suspect, the Flow ideas are downstream from games then it probably doesn’t really help us with game design. Game design is not a solved problem! “Make it fun, you know, like a game!” is not especially actionable advice, because figuring out how to make a game fun is itself a difficult art.

chriddi, moecki and/or the-gorilla

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit